Climate Change: The Road Ahead

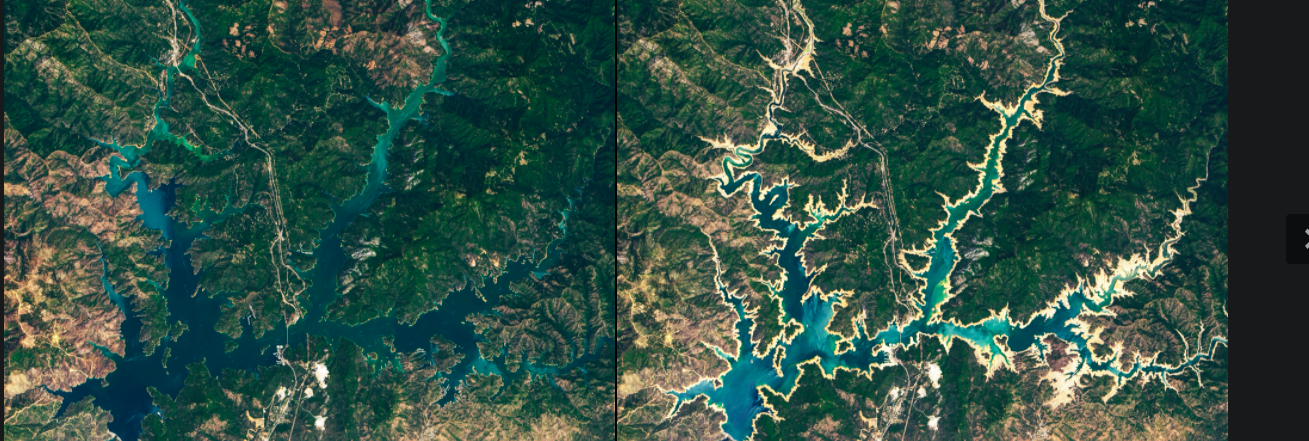

Earth is facing a catastrophic climate emergency, according to 14,000 scientists from 153 countries. Six years ago, most nations of the world agreed in Paris to collaborate on fighting the most urgent threat to our way of life and take action to limit the Earth’s average global temperature to 1.5 degrees celsius above pre-industrial levels. Today, as North America is still reeling from an unprecedented Heat wave, China experiences catastrophic floods, Europe suffers from both floods as major rivers burst from unexpected rain and drought-facilitated wildfires from Portugal to Turkey; Pakistan declares some populated regions to become uninhabitable for humans within the next 5 years and one solemn truth is undeniable: We have entered the age when the catastrophic scenarios of past predictive models are becoming reality around the globe. And yet the debate remains politicized and tangible action timid.