Identity and Power: Consequences of the Turkish Elections

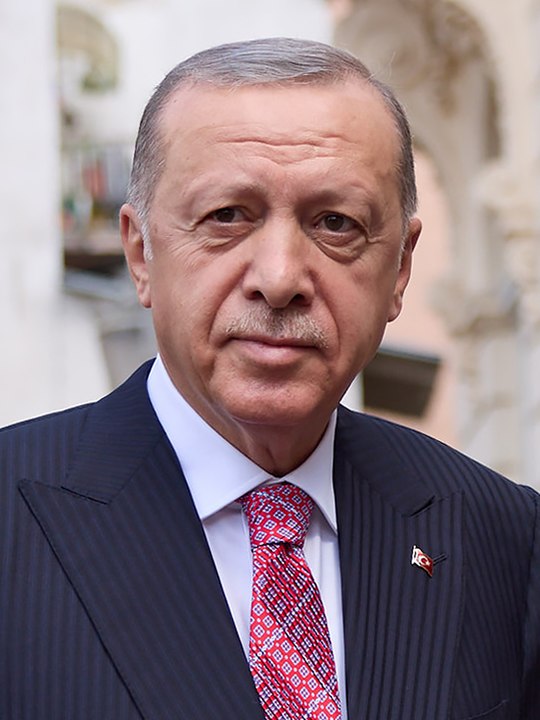

The fate of the Turkish republic hung in the balance as it held general elections on on May 14th. This general race determined not only the composition of the parliament but also the position of the presidency, which has been by direct popular vote since the 2007 constitutional referendum. The incumbent president, who has been a predominant figure in Turkish politics since 2003, is Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He runs the religious conservative Justice and Development party. History was made in the election as this was the first time ever that Erdogan failed to decisively win the first-round election for the presidency.

President Erdogan fell just shy of avoiding a runoff at about 49 percent of the vote while his party and its electoral allies won 323 seats in parliament out of 600. His main opponent Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu of the left wing secular Republican People’s Party managed to score an impressive performance at about 45 percent of the vote. Kılıçdaroğlu’s party, which was founded by Kemal Ataturk, the father of the Turkish republic, and its electoral allies only got 212 seats. An unprecedented presidential run off is scheduled for May 28th when the aforementioned frontrunners will face off again. In truth, despite this being Erdogan’s most lackluster presidential run, he outperformed expectations and is favored to win the runoff given that the third place candidate’s base ideologically leans toward Erdogan.

The election came amid a host of problems for Erdogan. The country, a major economic power, is suffering from a high, albeit declining, rate of inflation which is projected to be at 46 percent by year’s end. Furthermore, there was major criticism over his government’s conduct over how it prepared for and handled the recent major earthquake. The longevity of the Erdogan era has borne witness to major political changes in Turkish politics and this election partly reflected the ongoing transformation of Turkish identity.

To understand how much Turkey has changed, it behooves one to look back to the foundation of the republic. When Kemal Ataturk was proclaimed by the Turkish parliament as the first president of the Turkish republic in 1923, he wanted to build a secular and Westernized country whose territorial integrity was respected and who had no significant quarrel with any major foreign power. It was to achieve that end that he fought a war of independence against the old Ottoman Empire and its allied powers to safeguard what he regarded as Turkey’s full territorial sovereignty. He abrogated part of the 1920 Treaty of Sevres, which had partitioned pieces of modern day Turkey between Greek, Italian, Armenian, and Kurdish powers, and replaced it with the more favorable 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.

Ataturk’s reforms were widespread and dramatic. He abolished the caliphate, the office of the religious head of the Islamic faith. He replaced religious laws with secular civil and criminal codes, banned religious symbols from government offices, and replaced the Arabic script with a Latin one for the Turkish language. Ataturk’s foreign policy can best be reduced to his famous adage: “peace at home, peace in the world”- which was a proclamation of neutrality in foreign affairs. This neutrality proved, however, to be tilted toward the West. This movement toward the West would be best exemplified in the fact that 14 years after Ataturk’s death, the country would join the American-led North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1952. Ataturk’s relationship with his country’s Kurdish population was a contentious one as demonstrated by the revolts by the Kurds in the 1920s and 1930s against his regime. This atmosphere of tension between the Kurds and Ankara has continued in one form or another to the present day.

While Ataturk professed a desire to democratize Turkey, the first free and fair elections for parliament were only held in 1950, which was after his death. It ought to be emphasized that the 1950 election was described by one Middle Eastern scholar, Bernard Lewis, as the first of its kind in the Middle East, where a government voluntarily ceded power after losing an election. However, Lewis caveated this by observing that the new leader “soon made it clear that he was determined not to leave by the same route [i.e. through elections] which he came [into power]". Turkish democracy would come in fits and starts throughout its history with military coups and accusations of civilian-driven authoritarianism disrupting the process. The latest attempt by segments of the Turkish military to drive an elected government from power was in 2016.

When Erdogan took power in 2003 (through democratic means), he inherited much of this legacy of laïcité and general policy of good neighborliness that was built up by Ataturk and his successors. Indeed, his own party’s foreign policy motto has been “zero problem with neighbors”, which followed in the belief that trade would enhance Turkish influence. Erdogan initially pursued a policy of greater political and social rights for Turkey’s Kurdish population, but this broke down in 2012 along with the peace process. His country has jailed the leader of a mainstream pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) since 2016, and his government sought to ban the pro-Kurdish party outright since 2021 over allegations of its connection to outlawed Kurdish militias. This has ironically caused the Kurdish voter base for the HDP to align themselves with the old Kemalist party.

Erdogan has nevertheless fundamentally altered the character of the Turkish state. Whereas Ataturk was the great secularizer, Erdogan has proven to be the great traditionalist. Since the 1990s, Erdogan has belonged to political parties that advocated for a more permissive role of religion in the state. Erdogan has pushed for greater funding for Islamic schooling in Turkey, explaining that he wants to create “a pious generation.” He has also lifted the hijab ban on women in government jobs and said of the repeal that it ended “a dark time”. Whereas Ataturk looked to break from the Ottoman past, Erdogan embraces it. In that vein, the 21st century’s Turkish politico restored the teaching of the old Arabic-based script of the Turkish language. Erdogan has also reveled about the faded glory of the Ottoman past. In foreign policy too, Erdogan has sought to break from a reflexively pro-Western line and tries to act as a balancing power in the region and world. This would for instance explain his off and on again relationship with the State of Israel and his differing stances toward Russia. He has also taken a much more aggressive foreign policy stance: Turkey has engaged in military operations in Syria, Libya, and Iraq multiple times since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war. The Syrian and Iraqi operations were done based on Turkish fear of the Kurdish powerbase in northern Syria and northern Iraq alleging ties with Turkish Kurdish insurgent groups.

Would Erdogan’s main election rival from the Kemalist party break from his policies if elected? This depends on the issue. In terms of foreign policy, Kemal Kilicdaroglu promised that he would not seek to fundamentally upset friendly relations with Russia and would be open to serve as a mediator for peace between Russia and Ukraine. While a top opposition foreign adviser said that Kilicdaroglu, if elected, would pursue “dialogue and a non-interventionist approach” in regional affairs as opposed to Erdogan’s more aggressive approach, he like Erdogan plans to normalize relations with Syria. In terms of relations with Israel, there is little to suggest that Kilicdaroglu would pursue a more friendly path than Erdogan. When former president Donald Trump recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, Kilicdaroglu, then a member of parliament, remarked “If you [Erdogan] want to sever ties [with Israel], then go ahead. We are backing you.” He also repeated anti-Israel narratives about the Mavi Marmara affair as late as 2022 after Israeli president Herzog visited the country. Several of his major allies in parliament have decried the current détente between Turkey and Israel and accused Erdogan of betraying the Palestinian cause.

Erdogan has changed the Turkish republic through de-secularizing its character and making it more appreciative of its Ottoman and Islamic past. In some ways though Erdogan has carried on certain inheritances from the Kemalist past in terms of a tense relationship with the Kurds. While his main political rival for the president may be much more tilted toward the West and decrying the democratic deficit in the country (which does have rings of truth to it), even if Kemal Kilicdaroglu manages to achieve an electoral upset in the second round there are some items of consensus between the main parties. Erdogan’s era , however, is likely to continue as he is the favorite to win the second round of elections.