To Join, To Defect, Or To Reject: What April’s Elections Reveals About International Coalitions On Russia

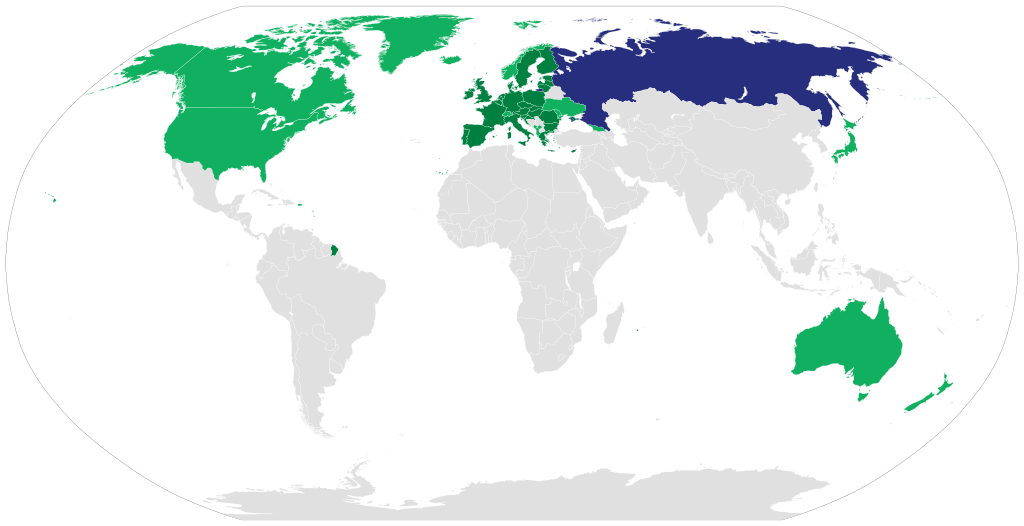

As the European Union (EU) and the United States continue their sanction regimes against the Russian Federation over its war in Ukraine, it is important to gauge whether the public supports these various measures. Sanctions are an imperfect instrument of foreign policy and often carry two-way costs. More often than not the declared object of sanctions fails to be met. One such example can be seen in the Russian currency, which was touted as worthless when sanctions first kicked in, yet as of the writing of this article, the Ruble has rebounded in value to its pre-sanctions levels, and Putin’s popularity has skyrocketed to over 80 percent since March. Neither regime change in Russia nor severely undercutting Russia’s ability to conduct the war has yet to be achieved. Whether there are rejections or potential defections from the pro- or anti-Russia sanctions coalition in terms of who the public decides to elect is vital to see if the sanction regime will expand, stagnate, or fall apart. The Hungarian, Serbian, and French elections in April illustrate the limited extent of public support for the costly anti-Russia sanctions, and in Pakistan, the ousting of former prime minister Imran Khan presents the possibility for a potential defection toward the West’s sanctions regime. In the case of France it should be noted that at the time of the writing of this article that the sole election available to be analyzed was the first round of their presidential elections.

On April 3rd, Victor Orban, won re-election to a fourth term as the Hungarian Prime Minister, a position he has held since 2010. Not only did he manage to win re-election in what was predicted by many pollsters to be a close race between him and the united opposition party, but his party won an expanded 2/3rds majority in the parliament. The united opposition party lost seats and a new party that is further to the right than Orban’s nationalist coalition got seats in parliament. The head of the united opposition party did not even win in his own district. In Orban’s victory speech, he mocked those outside forces whom he saw trying to influence the outcome of the election like EU bureaucrats and President Zelensky of Ukraine. Orban is a well-known opponent of sanctions against Russia.

Orban’s main opponent and head of the united opposition party, Peter Marki-Zay, ran on a pro-EU and pro-Zelensky platform. Marki-Zay conceded while complaining that the elections were not truly free or fair. He claimed that the opposition did everything right in the election but that the results showed that Orban can always win elections due his “12 years of brainwashing” the public. The Organization for Security and Co-operation In Europe (OSCE), a third party observer of the Hungarian elections, reported that the election was well run and that it offered real alternatives to the public but that the Hungarian media coverage was marred by bias and the campaign funding was far from transparent. Two days after Orban’s landslide victory, the EU, which Hungary is a part of, announced that it is launching a rule of law disciplinary procedure against Hungary that may result in sanctions being levied against it.

The origins of controversy between the EU and Orban can be traced to his vision of Hungary as an illiberal democracy: in 2014, Orban gave a speech where he lambasted the liberal values of today as being ill suited for Hungary given that liberal values were self-destructive and were undermining national interests. Such criticism of liberal values has caused many to be concerned. Just last July, Reporters Without Borders issued a statement claiming that oligarchs close to Orban’s party controlled 80 percent of the domestic media. In 2020, the parliament passed a law that criminalized the spread of what was deemed misinformation concerning the government’s actions to contain the coronavirus. Similarly, the parliament also voted in March of 2020 to temporarily grant Orban emergency powers to rule by decree in order to combat the coronavirus. This law was repealed in June 2020.

Elections in the Republic of Serbia largely followed Hungary’s example. Incumbent President Aleksander Vucic won nearly 60% of the vote, and his party, the Serbian Progressive Party, won a large plurality of the vote (43%) for seats in parliament. The OSCE noted that the 2022 Serbian elections largely respected fundamental freedoms and offered diverse choices to the public while criticizing the candidate’s unbalanced access to the media, undue pressure put on public servants to vote for the government, and unequal campaign resources. Vucic has taken a nationalist line during the entire Ukraine crisis and has refused to participate in sanctioning Russia. Nationalist parties to the right of the Serbian Progressive Party also won 17.6% of the vote for seats in parliament. Only in 2008 did these right-wing parties perform better. Indeed, a poll taken after the election showed that for the first time in Serbia, more people are against joining the EU than in favor. It is largely expected that Vuvic’s Progressive Party will enter into another coalition agreement with the Serbian Socialist Party to garner a parliamentary majority. Moreover, in this election the Socialists aided Vucic by not fielding a presidential candidate.

It is in France where a key defection is at risk from the international sanction coalition. Polls predict a shockingly close election in the second round between the current French president Emmanuel Macron and his challenger from the right Marine Le Pen. Indeed, anti-establishment candidates from both the French right and left wings got a predominant share of the electorate during the 1st round. Macron managed to win a plurality of the vote with about 27.9%, which was followed by Le Pen’s share of about 23.2% of the vote. Le Pen in the first round was followed by Melenchon, the main outsider candidate from the left, getting about 22% of the vote, and Zemmour, another outsider candidate from the right, garnering about 7.1% of the vote. The anti-establishment vote share between their three main candidates combined to approximately 52.3% of the vote. Many of these and other anti-establishmentarian candidates ran on a platform that was both EU and NATO skeptical. Marine Le Pen and her party have voiced the idea of a French-NATO rapprochement with Russia, raised concerns of the backlash in costs that some of the sanctions on Russia will cause in France, rejected prospective sanctions on Russian oil and gas, and has expressed reservations on sending arms to Ukraine. Le Pen has also raised the prospect of transforming the European Union - which she views aspects of as unconstitutional, anti-democratic, and anti-nationalistic - into a more devolved Association of Free Nations of Europe.

A second round of elections between just Macron and Le Pen will now happen after the first as no candidate got a clear majority of the vote. The second round of presidential elections between Macron and Le Pen is unlikely to result in a repeat of the +30% margin of Macron’s 2017 landslide victory against Le Pen. Since the 1st round, Zemmour has endorsed Le Pen in the runoff while Melenchon called for his supporters to not vote for Le Pen. In Melenchon’s case, however, a survey of his voter base (page 20) shows that 25 percent would vote for Le Pen, 34 percent would vote for Macron, and 41 percent would simply not vote. If polls are to be believed, the election between the two this time will be narrower than in 2017. Should Le Pen, who has popularity issues like Marcon of her own, fail to win the second round it will be because, as the voter survey suggests, she was unable to unite the anti-establishment vote. Nevertheless if Le Pen upends the odds and wins the second round then it is possible to see France defect from the Russian sanctions regime. Should Macron win in the presidential race, but see his party suffer heavy parliamentary defeat in either number of seat changes in parliament itself or through the popular vote to populist parties like Le Pen or Melenchon’s parties in the upcoming elections, then France’s foreign policy may likewise be moderated to take better account of the anti-war and anti-sanctions sentiments within the French electorate. Alternatively, given the weakening of the centrist parties and candidates in France, should this trend continue even if Macron and his party manage to win the upcoming elections in 2022, an outsider candidate with less baggage than Le Pen could win next time around.

In Pakistan, after the first parliamentary motion of no confidence against the Prime Minister, Imran Khan, and a call on April 3rd by the Prime Minister for the dissolution of the national assembly faltered, a second motion of no confidence against the government succeeded by a razor thin margin. These motions of no confidence were initiated by the opposition largely on charges of the government mismanaging the economy. The now former Prime Minister Khan alleges foreign collusion in a conspiracy to bring him and his government down. He has in particular singled out Donald Lu, an American official within the State Department, as the facilitator of this effort to remove him. Imran Khan has been an advocate for greater alignment with Russia and China, he has refused to levy sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine, and he has also refused to condemn the invasion. For its part, the Pakistani military (in particular the Inter-Services Intelligence agency), which is often accused of meddling in the internal politics of the country itself, has denied that any foreign or military conspiracy played a part in the ouster of Khan. However, sources within the Indian military have reported that the Pakistani military was increasingly dissatisfied with growing ties to China over the United States as the quality of military goods from China were in their judgment inferior to that of the goods they received from the United States. It should be noted amid this alleged coup, that a number of retired military officers have been supportive of Khan and were critical over the way he was ousted. This highlights that Khan has support among those with influence on certain circles in the Pakistani military. This in turn could spell a potential schism between the military should Khan try to press his claim to the premiership through undemocratic means or should the new Prime Minister try to use the military to deny Khan a chance to democratically undo his ouster.

Shehbaz Sharif, the new Prime Minister of Pakistan, who is from the Pakistan Muslim League party (which is not Khan’s party), was elected by the parliament on April 11th amid the resignation of over 100 Khan aligned lawmakers from parliament. Sharif is known for being a more pro-Western figure than Khan. There is however an open question over how much he can move Pakistani foreign policy and whether he will try to take a neutral rather than a friendly approach toward the West. The fact that Khan’s party did better than expected in local elections before the first motion of no confidence vote happened may present a further headache for the pro-Western elements in Pakistan. A poll of Pakistanis prior to his ouster, showed that Khan’s party would win a plurality of seats in parliament (see page 18 of the poll). Since his ouster, Khan has also held well attended political rallies. Put simply, Khan’s political career is not at an end, and he could be returned to power in the October 2023 elections, especially if the economic status of the country does not improve significantly.

While foreign policy may not be amongst the most important political issues a voter considers when they cast their ballot, these various April elections reveal that many voters were comfortable with a party that advocated a less hostile policy toward Russia. The Hungarian and Serbian elections showed that the public trusts the incumbent governments to maintain their neutral course in the dispute over Russia and that parties that advocated an anti-Russian policy were largely rejected by the public. In those two cases, the voters rejected the opportunity to get further involved in the sanctions regime against Russia. Indeed, in Hungary’s case, Orban boasted about the fact that he had beaten off Zelensky’s attempt to shame him and his country into a different policy direction over Russia. France is a potential case of coalition defection depending on how the second round of elections for the presidency and the parliamentary elections goes. Already in the first round of elections, parties that were skeptical of NATO, the EU, and the sanctioning of Russia captured the majority of the share of the electorate. Should Le Pen, who has framed the sanctioning of Russia as a cost-of-living issue for France, succeed and/or should outsider parties get a significant share of seats in parliament then such a course change is possible. The possibility that economic sanctions could destroy the living standards for those levying the sanctions has been acknowledged in the United Kingdom and in Germany. Such economic effects could mean that further defections in Europe are entirely possible if not probable at some point. Pakistan emerges as a potential new member of the sanctions regime but even here, the new Prime Minister (who was appointed through parliamentary maneuvers) has made cautious statements about his vision of foreign policy, and it is also possible here that Khan will regain the premiership and continue his policy of closeness toward China and Russia.